A joint article by both myself and Ellie Taylor, a fellow Ways of Working Enablement Specialist here at Nationwide.

The Golden Thread

As we start a new year, focusing on outcomes has been a common topic of discussion in our work in the last few weeks.

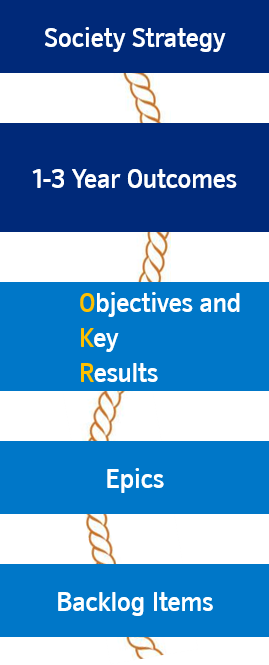

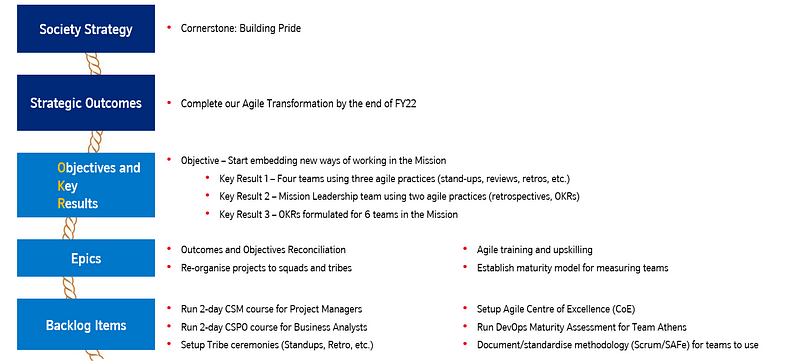

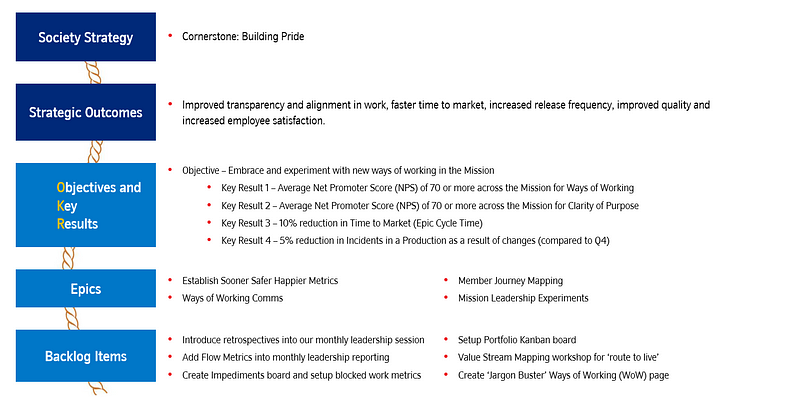

Within Nationwide, we are working towards instilling a ‘Golden Thread’ in our work — starting with our strategy, then moving down to three year and in-year outcomes, breaking this down further into quarterly Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) and finally Backlog Items (and if you’d like to go even further — Tasks).

This means that everyone can see how the work they’re doing fits (or maybe does not fit!) into the goals of our organisation. When you consider the work of Daniel Pink, we’re really focusing here on that ‘purpose’ aspect in trying to instil that in everything we do.

As Enablement Specialists, part of our role is to help coach the leaders and teams we work with across our Member Missions to really focus on outcomes over outputs. This is a common mantra you’ll hear recited in the Agile world, with some even putting forth the argument that it should in fact be the other way round. However, orientating around outcomes is our chosen path, and thus we must focus on helping facilitate the gathering of good outcomes.

Yet, in moving to new, outcome oriented ways of working, a pattern (or anti-pattern) has emerged— one of which is the concept of a ‘committed outcome’.

“You can’t change that, it’s a committed outcome”

“We’ve got our committed outcomes and what the associated benefits are”

“Great! We’ve got our committed outcomes for this year!”

This became a hot topic amongst our team — what really is an outcome and is it possible to have a committed outcome?

What is an Outcome?

If we were to look at a purely dictionary definition of the word, an outcome is “something that follows as a result or consequence”. If you want help in what this means in a Lean-Agile context, the book Outcomes over Output helpfully defines an outcome as “a change in human behaviour”. Which we can then tweak for our context to mean ‘something that follows as a result or consequence, which could also be defined as a change in member or colleague behaviour’.

However this definition brings about uncertainty. How can we have certainty over the outcomes given they’re changes in behaviour? Well a simple way is to call them committed outcomes. That way we’ll know what we’ll be getting. Right?

Well this doesn’t quite work…

Outcomes & Cynefin

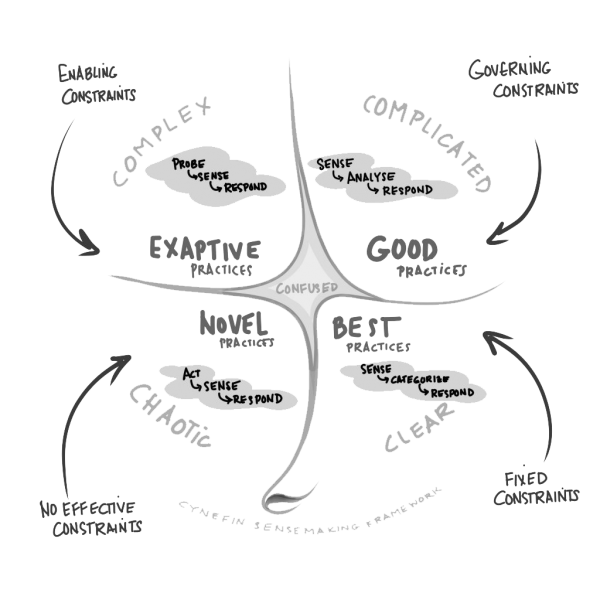

This is where those focused in introducing new ways of working and particularly leadership should look to leverage Cynefin. Cynefin is a sense-making model originally developed by Dave Snowden to help leaders make decisions by understanding how predictable or unpredictable their problems are. In the world of business agility, it’s often a first port of call to help us understand the particular context teams are working in, and then in turn how best to help them maximise their flow of work by selecting a helpful approach from the big bag of tools and techniques.

The model introduces 4 domains: Clear, Complicated, Complex and Chaotic, which can then be further classified as predictable or unpredictable in nature.

There is also a state of Confused where it is unclear which domain the problem fits into and further work is needed to establish this before attempting to identify the solution.

Source:

Both Clear and Complicated problems are considered by the model to be predictable since they have repeatable solutions. That is, the same solution can be applied to the same problem, and it will always work. The difference between the two being the level of expertise needed to solve.

The solution to Clear problems is so obvious that a child can solve it, or if expertise is needed the solution is still obvious and there’s normally only one way to solve the problem. Here is where it’s appropriate to use “best practice”. [example: tying shoelaces, riding a bike)

In the Complicated domain, more and more expertise is needed the more and more complicated the problem gets. The outcome is predictable because it has been solved before, but it will take an expert to get there. [example: a mechanic fixing a car, a watchmaker fixing a watch]

The Complex and Chaotic domains are considered unpredictable. The biggest difference between the two from a business agility perspective is whether it is safe to test and learn; ‘yes’ for Complex and definitely ‘no’ for Chaotic.

Complex problems are ones where the solution, and the way in which to get to that solution (i.e. the practices) emerge over time because we’ve never done them before, in this context, environment, etc. Cause and effect are only understood with hindsight, so you can only possibly know what happens and any side-effects of a solution once created. The model describes this activity as probing, trying out some stuff to find out what happens. And this is key to why this domain is a sweet spot for business agility. We need to try out something in such a way, typically small, that ensures that if it doesn’t work as expected, the consequences are minimised. This is often referred in our community as ‘safe to fail.’

And finally, Chaos. This is typically a transient state; it resolves itself quickly (not always in your favour!) and is very unpredictable. This domain is certainly not a place for safe to fail activity. Decisive action is the way forward, but there is also a high degree of choice in the solution and so often novel practices emerge.

Ok, so what’s the issue?

The issue here is that when we think back to focusing on outcomes, and specifically when you hear someone say something is a committed outcome, what’s more likely is that it’s a (committed) output.

It’s something you’re writing down that you’re going to ‘do’ or ‘produce’. Due to the fact that most of what we do sits in the Complex domain, we can’t possibly know (for certain) whether what we are going to ‘do’ will definitely achieve the outcome we’re after until we do it. We also don’t even know if the outcome we think we are after is the right one. Thus, it is nonsensical (and probably impossible!) to ‘commit’ to it. It’s unfortunately trying to apply thinking from the Clear domain to something that is Complex. This is a worry, as now these outcomes become something that we’ll do (output) rather than something we’ll go after (outcome).

In lots of Agile Transformation or Ways of Working initiatives, this manifests itself at team level where large numbers of Scrum teams are stuck in a world where they still fixate on “committed number of items/story points” — ignoring the fact that this left Scrum ten years ago. Scrum Teams commit to going after both long-term (product) and short-term (sprint) goals, expressed as outcomes, with the work they do in the product/sprint backlog being how they’re trying to go after those. They do this because they know their work is complex. The same goes for the wider organisation wide ‘transformation’, which is treated as a programme where, by a pre-determined end date (usually 12 months), we will all be ‘transformed’. This of course can only be demonstrated in output (number of teams, number of people trained and certified, etc.) due to the mindset it is being approached with.

The problem with committing to an outcome (read: output) is that it stifles empowerment, creativity, and innovation, turning your golden thread from something meaningful, purposeful that celebrates accountable freedom, to output oriented, feature factory measured agile theatre.

Ultimately, this means any new ways of working approach is likely to be sub-optimal at best — it’s a pivot without a pivot, leading to everyone in the system delivering output, delivering this output faster, yet perplexed at the lack of meaningful impact. Meaning we neglect the outcomes and experimenting with many ways in our real desired results of delighting members and colleagues.

What we want to focus on are the problems we want to solve, which comes back to the member, user or colleague behaviours that drive business results and the things we can do to help nudge these. Ideally, we’d then have meaningful and, where appropriate, flow and value based measures to quantify these and track progress.

Summary

In closing, some key points to reaffirm when focusing on outcomes:

Outcomes are something that follows as a result or consequence

Cynefin is a sense-making model originally developed by Dave Snowden to help leaders make decisions by understanding how predictable or unpredictable their problems are.

Cynefin has 4 domains: Clear, Complicated, Complex and Chaotic, which can then be further classified as predictable or unpredictable in nature.

There is also a state of Confused where it is unclear which domain the problem fits into and further work is needed to establish this before attempting to identify the solution.

The work we do regarding change is generally in the Complex domain

As the work is Complex, there is no way we can possibly ‘commit’ to what an outcome will be as the relationship between the two is not known

Outcomes are things that we’d like to happen (more engaged staff, happier members) because of the work that we do

When you hear committed outcomes — people most likely mean outputs

Use the outputs as an opportunity to focus on the real problems we want to solve

The problems we want to solve should come back to the member, user or colleague behaviours that drive business results (which are the actual ‘outcomes’ we want to go after)

What do you think about when referring to outcomes?

Have you had similar experiences?

Let us know in the comments below or tweet your thoughts to Ellie or myself :)